If you’re headed North on the Sterling Highway, passing through the modest community of Cooper Landing, you notice a lot of things, both old and new. The road still winds its way around the gentle bends of the glacial green Kenai River, and the majestic peaks of the Kenai Mountain Range still scrape the sky all around you. Some of the same old businesses are still around and thriving, but there are some new ones, too. The speed limit is still a plodding 35, much to the chagrin of anyone in a hurry. And the shores of the Kenai Lake still boast one of the most breathtaking views in the already beautiful State of Alaska.

There is one change, though, a big one that you just might miss heading toward Anchorage or Seward unless you chance a glimpse in your rearview mirror. That gap in the forest on your left. It used to be just a wall of rock and trees, but now it’s a sprawling, yet clearly uniform, opening that rises up and into the mountains. It’s as though the squared head of a giant gravel shovel carved a path through the once-dense foliage–an apt metaphor, to be sure.

Driving South, though, you get a much better view, if only a brief one as you zip by, of the foundations of Sterling Highway MP 45-60, more colloquially known as the Cooper Landing Bypass.

The massive infrastructure project has been discussed for decades. For many of those years, passers-by would glance north at the mountains as they drove along and wonder what a project of that magnitude might look like someday. Then, in 2014, talks of the new road’s development became more serious when the Alaska Department of Transportation brought the initial stages of the Bypass to the public in a Draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement, but the project would still have to complete a series of public comment stages and revisions before it would break ground. Fast forward to 2020, and the Bypass finally saw its initial clearing operations get underway.

It’s been welcomed by some, criticized by others, but has nevertheless become a part of the Cooper Landing landscape. The question these days, though, is how long its contribution to that landscape will be one of gravel and dust and when the now $844.5 million expenditure will become one of sleek, modern infrastructure complete with all of its promised luxury and convenience.

But let’s back up a moment. Before getting angry trying to tackle that question, it’s worth zooming out and taking in the full breadth of such an expansive undertaking.

A project scope that’s much more than you realize

As you crest the first hill heading up into the East side of the project, the first word on everyone’s lips is, “Wow.” The sight really is impressive, and getting your first look at the actual scope of the Bypass immediately lessens the sticker shock.

The wide swath of subgrade, almost entirely composed of repurposed materials taken from the project area during the clearing, blasting, and excavation processes, extends once again beyond line of sight. You can’t really call it a road yet since it is, for now, just a drivable surface for equipment to traverse the construction area, but to the untrained eye, it looks like asphalt could be just a few months away.

According to Project Engineer, Shaun Combs, though, that’s not quite the case. There is still a substantial amount of work that needs to be done before the project is ready for paving and regular traffic.

Combs has been overseeing the Bypass’s construction since 2020. With the project under a microscope after a 2023 assessment bumped its price tag from $350 million to $840 million, Combs’s role as Project Engineer-by-Day-Tour Guide-by…well, also by day, has expanded quite a bit. Since that $500 million change, the project has seen a steady stream of guests and dignitaries wanting to get eyes on the source of such consternation. He fields question after question with practiced ease, offering one eye-popping project fact after another.

“We have [already] moved approximately a little over 3 million cubic yards of material,” Combs said.

The most impressive part of that number is that the vast majority of that material is being repurposed and reused on the project itself. Combs says this type of construction is called “cut-to-fill” and is a very cost-saving means of building new roads.

Massive wildlife crossing culverts already installed or in the process of being installed will allow wildlife to move around and beneath the new road with ease and reduce disruption to their normal patterns.

When the project is complete, the public will also have new and more convenient access to trailheads, parking areas, and scenic overlooks.

“On the West side of the Juneau Creek Bridge, there’s going to be a new parking area on Forest Service land, and it’s going to have a horse trailer parking [area], RV parking, overnight vehicle parking, and that’s to access the Resurrection trail system,” Combs explained. “We also have the Bean Creek Trail system, a historical trail on the East side, and that’s also going to go through the corridor underneath the bridge too and tie back into its existing alignment.”

Speaking of the Juneau Creek Bridge, they say a beautiful bridge is like a diamond in a ring, and if early indications are correct, the new bridge will be a real wonder of Alaskan infrastructure once it is complete.

Extending more than 285 feet up from the bottom of the Juneau Creek Basin, the bridge might be the highest crossing in the state, surpassing the Hurricane Gulch bridge in Denali State Park.

Currently, the bridge is being constructed on the East side of the basin. Once ready, it will be rolled out and “launched” across the basin using a counterweight system to extend the bridge across open space until it can be lowered onto preset piers. The whole process of getting it in place can take as many as two to three days.

Upon completion, the bridge will be the longest single-span bridge built in the state since 1982 and the longest erected and launched bridge in Alaska’s history.

As of October 1, 2024, drilling for all of the abutments and pier location’s shafts, as well as all below-ground work for the drilled shafts (steel casings, reinforcing steel, and concrete), has been completed.

Work continues on the pier-drilled shaft locations, with the pier casing extensions expected to be completed by the end of October. Two large straddle cranes are being assembled in anticipation of structural steel delivery in the Spring of 2025.

According to the Sterling Highway MP 45-60 website, pier caps and abutments will be completed next Spring.

According to Combs, though, all of this work has only brought the project so far, and funding to continue is critical right now, so inflationary costs in the future don’t continue to balloon its overall ticket.

“It’s so paramount that we, you know, continue with the funding since we’re only part way there,” said Combs. “Granted, yeah, we moved 3 million cubic yards of material on both the East and West side, [but] that only got us to a certain elevation in the new roadway prism. The next stage is Stage 1B, which is on the East side. We have close to 2 million cubic yards of rock [material] and common [material] on the West side.”

The funding that wasn’t, but could have been

After visiting the Bypass, your first thought is: “This is going to be really beautiful once it’s done.” That thought is quickly followed by a second: “Wait, how is it that this isn’t supposed to be finished for another eight or more years?”

It’s a fair question, and the answer is perhaps the most troublesome, followed closely by the fact that the price tag has almost doubled, nearing a billion dollars.

The State has repeatedly assured the public that the Bypass will be funded with “discretionary grant funding.” It’s actually become something of a bureaucratic mantra. Every time the question is posed to anyone at the administrative levels of the Alaska Department of Transportation, you get the same answer: they are confident this project will be funded by discretionary grant funding and innovative financing.

Setting aside the vagary of a phrase like “innovative financing,” there is a significantly more important point to consider. Namely, if the eggs are all in the discretionary grant funding basket, where are the discretionary grant funds? Or, even better, where are the discretionary grant fund applications?

After a 2023 mega grant application for Sterling Highway MP 45-60 was not awarded, the DOT elected not to submit a grant application for the project in 2024. An interesting decision considering the state’s commitment to reassuring everyone that grant funding is the primary method of funding the project.

To be fair, grant funding can be a tricky process that is both complicated and highly competitive.

“It’s a competitive nationwide program,” says Ben White, Planning Lead for the DOT Central Region. “Most of the time, we’re limited to three applications per sponsor, and so the department submits two or three.”

White, who oversees DOT grant writing, said once a grant is submitted, it’s sent to the Federal Highways Administration (FHWA) in Washington, DC, where it, along with many other grants from all 50 states, undergoes a system of evaluations and analyses.

The grants aren’t all in the same basket, though, as the size of the project and the amount of the grant can vary greatly. Hence, the Bypass, given its $844.5 million price tag, falls into the “Mega Grant” category.

“These [are for] really large projects that are difficult to finance; they spread over many years, which is exactly the scenario we’re talking about,” said DOT Spokesperson Shannon McCarthy in 2023. “We’ll go ahead and try to secure funding through that program.”

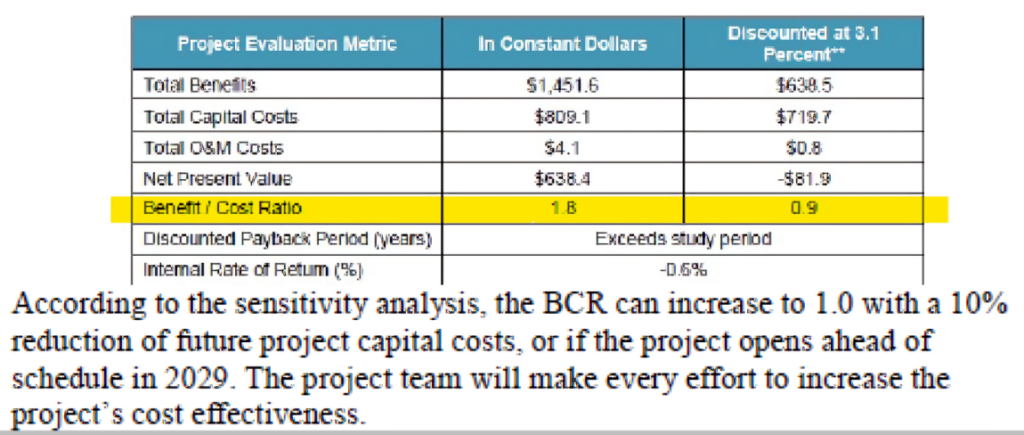

But according to White, it’s not quite as simple as apply for grant; receive grant. “Where we tend to fall short is when they do a cost-benefit analysis of the project.”

The cost-benefit analysis (CBA) of a grant application for the Bypass is the crux of both the problem of being awarded a grant and filing a worthwhile grant application at all.

A cost-benefit analysis boils down to two halves of a fraction that the grant writers attempt to bring as close to the whole number 1 as possible. On the bottom, the denominator is the cost of the project. The top then, the numerator, are as many key benefits the project will offer as can be outlined by grant writers. And herein lies the problem: state grant writers cannot bring the numerator, the benefit, to a value close enough to even out with the denominator, the cost, to submit a grant with a cost-benefit ratio that is near the sought-after total of 1.

This is why the 2023 grant application was denied. Surprisingly, the grant did actually advance to the second round of reviews, where the grants are awarded, something that sources within the DOT say they were not completely expecting. However, it was here that the CBA held up any further progress.

So, how does the DOT fix its cost-benefit problem in hopes of being awarded some of these discretionary grant funds? The short answer is that they can’t, not after certain decisions were made by Dunleavy administration-appointed officials.

The first decision that hamstrung the department’s ability to correct its CBA was pushing back the completion date of the project.

The planned Bypass completion date was initially set for 2025. That was later pushed back to 2028, and as of this year, it has been pushed all the way back to 2032, a full seven years later than the original plan.

So, how did the project get pushed back that much? That answer turns out to be a direct result of another decision made by the Dunleavy administration. Namely, its omission of the Bypass from the State’s 2024 Statewide Transportation Improvement Plan (STIP) amendment.

Every year, the FHWA distributes funds to all 50 states based on their Statewide Transportation Improvement Plans. However, not all of these funds are used, which means there is, in layman’s terms, money left over. This leftover money is then divided amongst states in an August redistribution, which is tied to their annual STIP amendments.

The Cooper Landing Bypass (Sterling Highway MP 45-60) was not included in Alaska’s 2024 STIP Amendment.

Thus, the amount redistributed by the FHWA to Alaska was unsurprisingly small: only $19 million. Not only was this amount nearly $90 million less than it received in 2023 when it received $108.2 million, but it was the lowest amount redistributed to any of the 50 states. For context, this means Alaska, with its 665,000 square mile size and 17,681 miles of roadways, received less money than the 1,034 square miles of Rhode Island ($19.4 million).

An important note here is that even if the CBA was corrected, the project still could not receive grant funding since it was not included in the amended STIP. So, if nothing else, removing the project from STIP in the 2024 amendment renders any potential for grant funding impossible presently.

One thing the decision not to include the Bypass in the STIP Amendment did accomplish was to dramatically increase the project’s overall cost.

Jonathan Tymick, the Project Manager for the Bypass, says that the DOT preconstruction manual dictates that projects should add 3% to their total cost annually for inflation. Tymick adds that by figuring in project risk calculations, expiring permits, and other similar factors, the new 2032 completion date hikes up the Bypass price by a substantial amount.

“Just by not putting this project in the STIP, we did add $120 million, you know, due to risk and inflation,” Tymick said.

According to the text within the 2023 Bypass grant application, which was, again, denied by the FHWA, in order to bring the benefit-cost ratio (BCR) near to a value of 1, one of two stipulations would need to be met: 1) “A 10% reduction of future project capital costs,” or 2) “if the project opens ahead of schedule in 2029.”

By choosing not to include the Bypass in its 2024 STIP Amendment and then pushing the project completion date back to 2032, the State double-shot this project in the foot. Not only did that one decision nullify its own path to reducing the project’s BCR to an acceptable number, but it also added significant cost to the project.

It is perplexing, then, to say the least, that state leaders continue holding fast to the notion that discretionary grant funding will swoop in to get such a massive project across the finish line. Either the administration is unaware of the project’s current BCR situation and its negative impact on potential grant funding, which is bad, or it knows the status of the BCR and is still expressing confidence in grant funding, which is worse.

A shift in infrastructure priorities?

But there is a separate piece to this puzzle that tells another, perhaps more illuminating, story—a project that was, surprisingly, included in the STIP Amendment: the West Susitna Access Road.

The West Susitna Access Road, a project in Gov. Dunleavy’s Mat-Su backyard, is so early in its development that it doesn’t even have an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). Yet, it was proposed to be allocated more than $80 million dollars for design and construction in the 2024 STIP. By comparison, the Bypass’s EIS, which finally received a signed FHWA Record of Decision in May 2018, dates back to the 1980s.

The decision to push the Bypass back eight years and to leave it out of the STIP Amendment in 2024 while leaving in a project like the West Susitna Access Road suggests a shift in infrastructure priorities from the Dunleavy administration, which has the final say on what is or is not included in the STIP and its annual amendments.

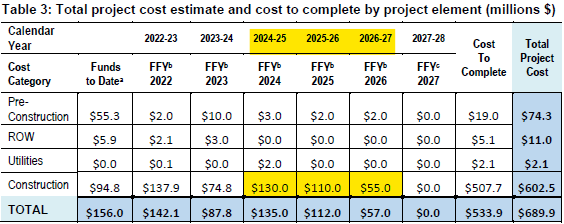

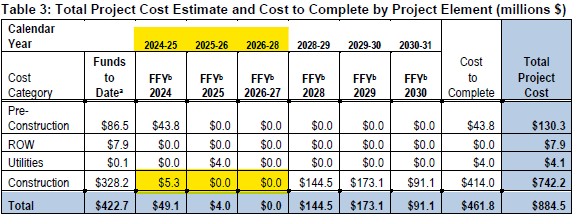

The veracity that such a shift exists is further substantiated when comparing the Bypass’s 2022 financial plan to its 2023 financial plan.

Annual project cost estimates in the 2022 financial plan funding trends show that the state intended to continue Bypass construction each year between 2024 and 2028 and presumably to its completion after a new STIP is in place in 2028. Compare that to the 2023 financial plan, however, which allocates only $5.3 million dollars to the project over the same period of time, and it would seem a shift in infrastructure priorities occurred between the drafting of the two plans. In fact, after 2024, the latter plan doesn’t allocate a single dollar to Bypass construction until 2028.

A cost estimate table from the Sterling Highway MP 45-60 2022 Financial Plan.

A cost estimate table from the Sterling Highway MP 45-60 2023 Financial Plan.

This re-prioritization of infrastructure projects and funds by the Dunleavy administration effectively takes an $840 million construction project (potentially even $1 billion or more) and places it squarely in the hands of a future administration. Meanwhile, fully unvetted projects like the West Susitna Access Road, which hasn’t even begun its environmental process, are taking precedence over the Bypass, which Tymick said has already undergone more than $400 million dollars worth of work.

Tymick added that if the project were included in the 2024-2027 STIP, it could be completed and opened to traffic in as few as four years for as little as roughly $290 million more in project costs.

But according to those within the department, the DOT does not prioritize any one infrastructure project over another.

“We have a lot of needs around the state,” said DOT Central Region Director Sean Holland. “Our program grew, but it didn’t grow enough to accommodate that inflation, really. And [the] cost of our projects has gone up significantly across the state. And we have this need, but we have needs all over the state.”

If all current plans remain in place, the Cooper Landing Bypass will likely end up costing more than $1 billion after initial estimates said the project would cost less than $350 million. In part, a substantial increase is to be expected, considering the initial estimate was figured prior to the explosive inflation associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, the state continues to demonstrate a lack of interest in completing a project in which it is already neck deep while simultaneously repeating a commitment to seeking federal funding it is not only unlikely to receive but has, at present, disqualified itself from completely.

One more note: Alaska is all too familiar with the concept of a bridge to nowhere. Phase 2 of the Bypass, the Juneau Creek Bridge, has already been apportioned all necessary funds and, regardless of future state or grant funding for the project as a whole, is anticipated to be completed in 2027.

If all things stay the same, in the very near future, a beautiful bridge will sit alone in the middle of the forests above Cooper Landing. Going nowhere.